golden chinkapin, giant evergreen chinkapin, chinkapin, chinquapin, golden-leaf chestnut

golden chinkapin, giant evergreen chinkapin, chinkapin, chinquapin, golden-leaf chestnut

- General Characteristics

- Biology & Management

- Harvest & Utilization

- Wood Properties

- Related Literature

- Oregon Producers and Users of Giant Chinkapin

This information was originally published in Hardwoods of the Pacific Northwest, S.S. Niemiec, G.R. Ahrens, S. Willits, and D.E. Hibbs. 1995. Research Contribution 8. Oregon State University, Forest Research Laboratory

General Characteristics

Giant chinkapin, an evergreen member of the beech family (Fagaceae), is the only tree-sized species of its genus found in the United States. Most of about 110 different species of Castanopsis occur in China, India, and Malaysia. With its dense, evergreen foliage (bright golden-yellow on the underside of the leaf) giant chinkapin is a distinctive, although minor, component of mixed-evergreen forests in western Oregon.

Giant chinkapin, an evergreen member of the beech family (Fagaceae), is the only tree-sized species of its genus found in the United States. Most of about 110 different species of Castanopsis occur in China, India, and Malaysia. With its dense, evergreen foliage (bright golden-yellow on the underside of the leaf) giant chinkapin is a distinctive, although minor, component of mixed-evergreen forests in western Oregon.

Size, Longevity, and Form

Mature giant chinkapin are typically 60 to 80 ft tall (150 ft maximum) and 12 to 30 in. in DBH (96 in. maximum). Chinkapin may live 400 to 500 years. In forest stands, giant chinkapin develops a dense, ovoid to conical crown on a straight, clear bole (50-70 percent of bole length). Chinkapin displays apical dominance even under open conditions. Open-grown trees develop a more spreading crown on a highly tapered bole. A shrub form of giant chinkapin is also common across the range of the species. Young giant chinkapins often develop a taproot, while older trees have a well- developed lateral root system.

Geographic Range

Giant chinkapin is native to the West Coast, from west-central Washington (lat 47° N) to central California (lat 35° N). The tree form of chinkapin is most common in the Coast and western Cascade ranges, from Lane County, Oregon to northern California.

Timber Inventory

The total volume of giant chinkapin in Oregon is about 86 MMCF (Appendix 1, Table 1) and is about equally divided between the West-Central and Southwest subregions. Another 50 MMCF occurs in the Northwest subregion of California. Most giant chinkapin in Washington are shrubs or small trees; their volume is negligible.

Biology and Management

Tolerance, Crown Position

The tree form of giant chinkapin is intermediate in tolerance. Chinkapins often occur in intermediate canopy positions, although they decline in vigor and may die after prolonged overtopping by associated conifers in older stands. Shrub forms of giant chinkapin are quite tolerant of shade and will persist in the understory.

Ecological Role

Giant chinkapin appears to be most competitive and persistent on droughty, infertile sites; this is where the oldest trees are usually found. Young chinkapins are also relatively aggressive and competitive during early succession on poor sites. Periodic disturbance (fire, logging, wind) may be required to maintain a component of giant chinkapin on better sites.

Associated Vegetation

Giant chinkapin rarely occurs in pure stands, but it is a minor component in many different forest types. Common associate trees are Douglas-fir, incense-cedar, sugar pine, Pacific madrone, tanoak, western white pine, western hemlock, white fir, ponderosa pine, California black oak, Port- Orford-cedar, canyon live oak, and knobcone pine. Common shrubs include Pacific rhododendron, salal, Oregon-grape, baldhip rose, dewberry, snowberry, oceanspray, hazel, poison-oak, manzanitas, modest whipplea, and prince’s-pine.

Suitability and Productivity of Sites

Giant chinkapin can grow relatively well on harsh, droughty, or infertile sites. Good growth and development of chinkapin can be expected on better sites, but management may be required to maintain chinkapin among taller, more competitive associates. The capability of a site for growing chinkapin should be evaluated by examining growth and form of older trees. Good growth potential is indicated by the following characteristics:

- Top height of at least 60 ft on mature trees

- Sustained height growth of 1 to 2 ft per year for ages 10 to 30 years

- Continuing diameter growth on mature trees.

Climate

Giant chinkapin grows in a mild climate characterized by winter rain and summer drought, wherein annual precipitation ranges from 20 to 130 in., with very little falling from June to September. Snow is common at higher elevations over chinkapin’s range, particularly in the Siskiyou Mountains and Oregon Cascade Range.

Judging from its superior competitiveness (relative to associated tree species) on harsh sites, giant chinkapin appears to have a high tolerance to extremes of heat, drought, and cold. The shrub form becomes more common under extreme climates.

Elevation

Chinkapin grows at elevations from sea level to 6000 ft.

Soils

The tree and shrub growth forms of giant chinkapin are found over a wide variety of soils derived from parent materials that include basalt, diorite, sediments, metasediments, and serpentine. The best development of giant chinkapin occurs on relatively deep soils that often have some nutrient deficiencies. The shrub form of chinkapin is predominant on shallow, rocky, droughty soils; the tree form is typically found on deeper soils and under more moderate moisture stresses.

Flowering & Fruiting

Trees of seedling origin produce sound seed at 40 to 50 years of age. Some fruiting occurs on younger stems; sprouts as young as 6 years old have produced seed.

Giant chinkapin is monoecious, and flowering usually begins in June or July. Male flowers form in dense catkins 1 to 3 in. long. From one to three female flowers develop within involucres either at the base of male flowers or separately on the stem. Flowers are pollinated by wind and perhaps by insects; chinkapin flowers are thought to impart a bad taste to honey.

The fruit is composed of one to three nuts within a spiny, golden-brown bur 0.6 to 1.0 in. across. Fruit ripens in the second autumn after pollination.

Seed

The seeds (nuts) are about 0.5 in. across and average about 830 to 1100/lb. Nuts are dispersed by gravity or by animals from September to December. Limited information indicates that germination rates are low (14 to 53 percent) compared to other hardwoods. Germination is not increased by cold stratification; however, seed germinates in spring under natural conditions.

Regeneration from Seed

Little is known of requirements for natural regeneration of chinkapin. Partial shade and a light litter layer appear to favor seedling establishment. In northern California, establishment of seedlings was best on moist sites with sparse understory vegetation. Initial growth of seedlings is slow (6 to 18 in. after 4 to 12 years).

Regeneration from Vegetative Sprouts

Giant chinkapin produces vigorous basal sprouts after cutting, fire, or other injury. To promote development of better quality sprouts, stumps should be cut low to the ground.

Regeneration from Planting

There are no documented cases of regeneration of chinkapin from planted seedlings.

Site Preparation and Vegetative Management

Little site preparation is necessary for establishing stands of sprout origin. Sprout regeneration and growth may be enhanced by burning or by mechanically removing slash that shades giant chinkapin stumps.

Site-preparation treatments that leave some leaf mulch and partial protection (debris, vegetation) may be best for promoting establishment and growth of chinkapin from seed.

The response of giant chinkapin to control of competing vegetation has not been studied. Vegetation management may be required to maintain chinkapin on more fertile or moist sites where other tree species will eventually suppress it in the absence of disturbance (historically, fire).

Stand Management

Giant chinkapin sprouts initiate at high densities, after which self-thinning and expression of dominance proceed rapidly. As with tanoak, thinning young sprout clumps (at ages 3 to 10 years) is probably not effective because of the abundant resprouts.

There is no information specific to managing giant chinkapin. As for other sprouting hardwoods, it is probable that growth and quality of stems may be improved by thinning in older stands of chinkapin.

Mixed-species Stands

Giant chinkapin is most commonly found as a minor associate in mixture with conifers. Particularly on better sites, periodic disturbance (or management) is required to maintain a component of chinkapin. Under these conditions, maintenance of more open stand conditions can allow chinkapin to grow tall, relatively well-formed stems.

Growth and Yield

There is no information on volume growth within pure stands or patches of chinkapin. A chinkapin component of 1100 to 1500 ft3 per acre comprised 11 to 21 percent of the total stand volume in 80-to100-year-old stands of Douglas-fir (site class III to IV) in three sample stands in the Coast and Cascade ranges. Average DBH of chinkapin in these stands ranged from 7.8 to 13.4 in.

Interactions with Wildlife

There have been few studies of the specific importance of giant chinkapin to wildlife. Chinkapin nuts probably provide a nutritious food for various birds and mammals. Typical chinkapin in the understory of conifer forests provide structural canopy diversity, which can improve habitat for various animal species.

Insects and Diseases

Insects and pathogens seldom cause serious problems for chinkapin. Heart rot fungi, including Phellinus igniarius, commonly cause defect in old or injured stems.

Insects such as the filbertworm (Melissopus latiferreanus) can have significant impacts on chinkapin seed crops. One study found that nearly 100 percent of the seed crop had been attacked by insects on one of three study sites. The California oak-worm (Phryganidia californica), which causes serious defoliation of oak species, also attacks chinkapin and reduces its growth.

Genetics

The shrub and tree growth forms of giant chinkapin may be genetically distinct in some cases. There appear to be three ecotypes of chinkapin: the tree form common at lower elevations, a high-elevation shrub type adapted to cold temperatures and heavy snow, and a chapparal shrub adapted to dry sites. Some hybridization may also occur between giant chinkapin and evergreen chinkapin (Castanopsis sempervirens).

Harvesting and Utilization

Cruising and Harvesting

Diameter at breast height and total height can be used with equations to estimate total tree volumes in cubic feet and sawlog volumes.

Log grades have been applied to giant chinkapin; there were large differences by log grade in the value of lumber recovered. Purchasers generally buy chinkapin as sawlogs (>10 in.) or pulp logs, without applying more detailed log grades.

Product Recovery

Sawlogs usually have a minimum small-end diameter of 10 in.; smaller logs are chipped for pulp. One study indicates that recovery of No. 1 Common and Better grade green lumber from giant chinkapin compares favorably to other hardwoods; however, Select and Better lumber has much lower recovery than other hardwoods (Appendix 1, Table 2). The relatively small volume of chinkapin that is harvested is fully utilized, and demand for lumber is high.

Wood Properties

Characteristics

The wood of giant chinkapin is of moderately fine texture and is moderately hard and heavy. The thin sapwood is the same color or slightly lighter than the light brown, pinkish-tinged heartwood. It is a ring porous wood with large earlywood pores that are generally singular or, occasionally, in pairs. Emanating radially from the large earlywood pores are flame-shaped clusters of smaller latewood pores not readily visible to the naked eye. Still finer are the pores across the growth ring and between the flame-shaped patterns. The rays are very fine and are barely visible with a hand lens. When the wood is dry, there is no characteristic odor or taste.

Weight

Chinkapin weighs about 61 lb/ft3 when green and 32 lb/ft3 at 12 percent moisture content (MC). The average specific gravity is 0.42 (green) or 0.48 (ovendry).

Mechanical Properties

Because of its limited availability and its uniqueness, giant chinkapin is rarely used for building or structural applications. Instead, it is most often used for fine furniture or exceptional paneling. Giant chinkapin performs well in these applications, if the furniture is adequately designed. See Appendix 1, Table 3 for average mechanical properties of small, clear specimens.

Drying and Shrinkage

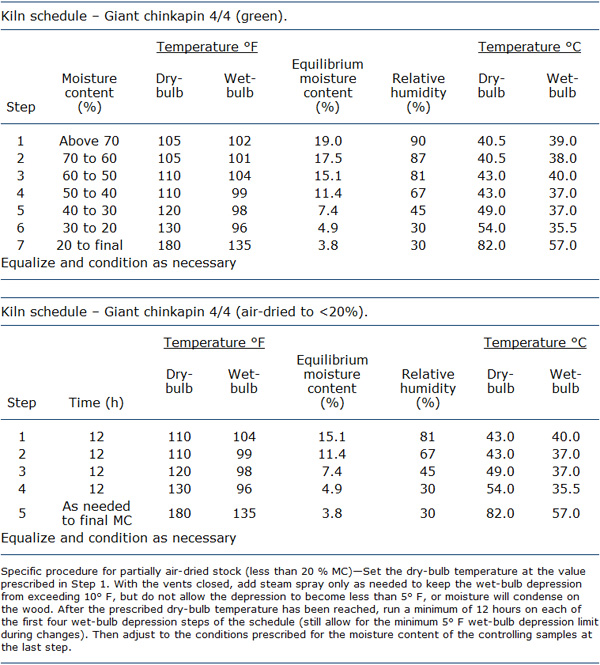

There are some distinct difficulties in kiln-drying green chinkapin. These, coupled with the uncommonness of this minor species, presently limit commercial availability. Much of the work on drying giant chinkapin was done before the mid-1950s, and indicated that chinkapin is subject to considerable collapse (excessive shrinkage in thickness) unless the wood is air-dried to below 20 percent MC before insertion into a kiln. Besides collapse, the defects of honeycomb and checking can be present. The first table below shows a schedule for drying green, 4/4 giant chinkapin. This schedule should be considered experimental; the final quality of lumber produced by this schedule is not well demonstrated. The second table shows a schedule that could be used if the material is first air-dried to the recommended 20 percent. For chinkapin, average initial MC is reported to be 134 percent (ovendry basis). The radial shrinkage (green to ovendry) averages 4.6 percent; tangentially, shrinkage averages 7.4 percent.

Machining

Giant chinkapin is a good wood for machining. It does not plane as well as the oaks or Pacific madrone, but there are fewer defects than with similar runs of walnut, red alder, and maple. Shaping and turning operations must be carefully controlled. Chinkapin sands well, with a minimum of both scratching and fuzzing.

Adhesives

Adhesives

Giant chinkapin bonds well with a wide variety of adhesives if conditions are moderately well controlled. The joint strength of chinkapin is considered to be excellent.

Finishing

From the limited literature on this subject, it appears that there are no apparent difficulties in staining or coating this wood. Its light brown color is very pleasant when clear-coated. Although filling is recommended for high-gloss finishes, the open grain characteristics of this wood allow for dramatic highlighting with glazes or lightly pigmented stains.

Durability

Information on the natural resistance of chinkapin to wood-decay organisms is very limited and conflicting. The heartwood is classified as nondurable in one source and “somewhat more than moderately durable” in another. Infestation with powder-post beetle (Ptilinus basalis) often occurs if the wood is stored improperly, and sap staining can affect its appearance.

Uses

Chinkapin is used for furniture, veneer, paneling, doors, and firewood.

Related Literature

HARRINGTON, T.B., J.C. TAPPEINER, II, and R. WARBINGTON. 1992. Predicting crown sizes and diameter distributions of tanoak, Pacific madrone, and giant chinkapin sprout clumps. Western Journal of Applied Forestry 7:103-108.

McDONALD, P.M., D. MINORE, and T. ATZET. 1983. Southwestern Oregon-northern California hardwoods. P. 29-32 in Silvicultural Systems for the Major Forest Types of the United States. R.M. Burns, tech compil., USDA Forest Service, Washington, DC. Agriculture Handbook 445.

McKEE, A. 1990. Giant chinkapin. P. 234-239 in Silvics of North America. Volume 2, Hardwoods. R.M. Burns and B.H. Honkala, coords. USDA Forest Service, Washington D.C. Agriculture Handbook 654.

PRESTEMON, D.R., F.E. DICKINSON, and W.A. DOST. 1965. Chinkapin log grades and lumber yield. California Agriculture Experiment Station, Berkeley, California. California Forestry and Forest Products No. 42.

ROY, D.F. 1955. Hardwood sprout measurements in northwestern California. USDA Forest Service, California Forest and Range Experiment Station, Berkeley, California. Forest Research Note 95. 6 p.